The Beach Boys Walking Tour of South London

This isn't a practical walking tour. It doesn't really cover much of South London, and it doesn't have all that much to do with the history of the Beach Boys. But I had the title stuck in my head, and found it kind of funny, so I've used it as a frame to write about 4 places and 4 songs which mean a lot to me.

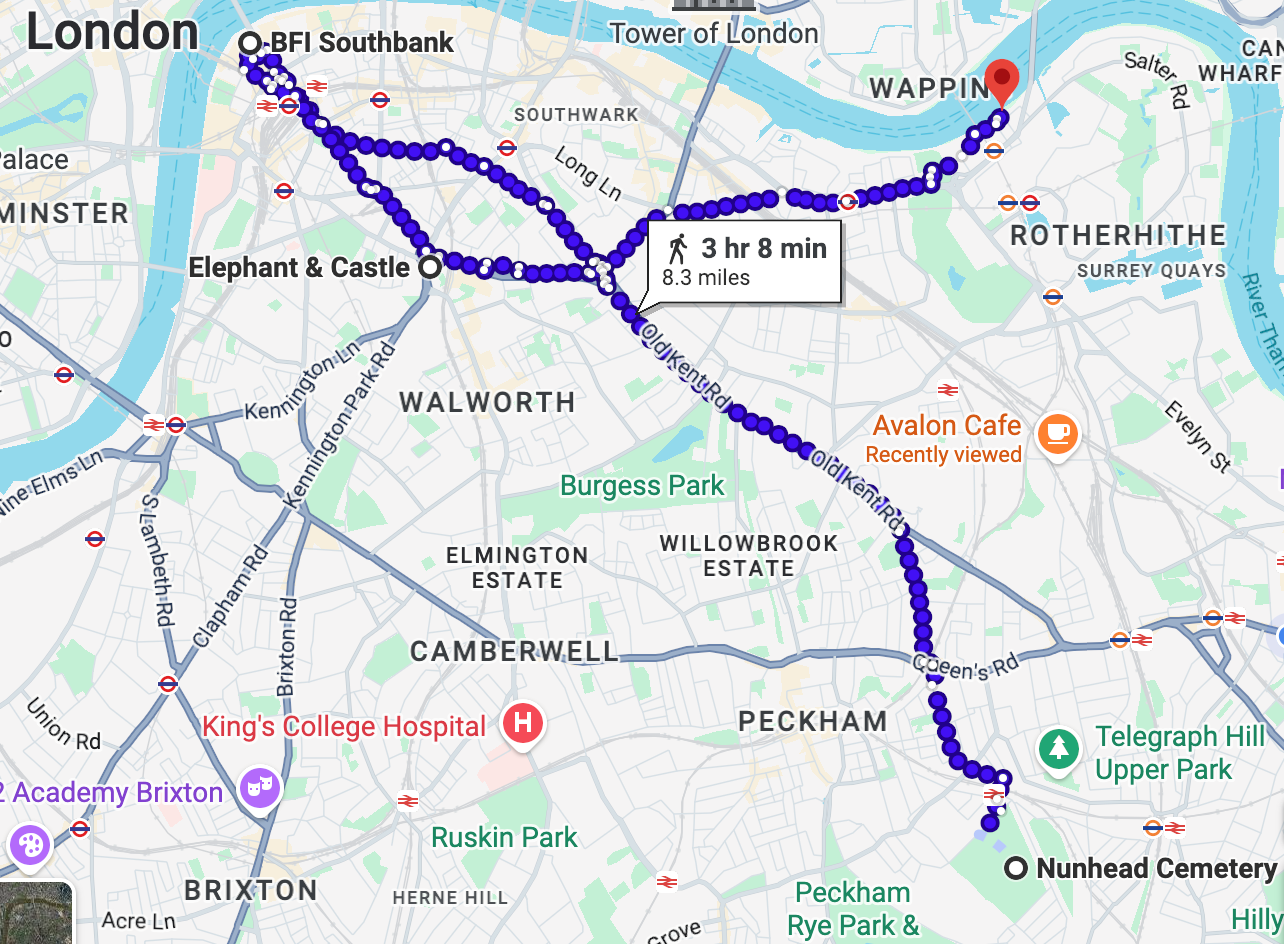

Google maps says that walking between these locations in this order will take about 3 hours. That's quite quick really, so expect a follow-up post someday when I've actually tried it out.

Nunhead Cemetery / A Day in the Life of a Tree (Surf’s Up)

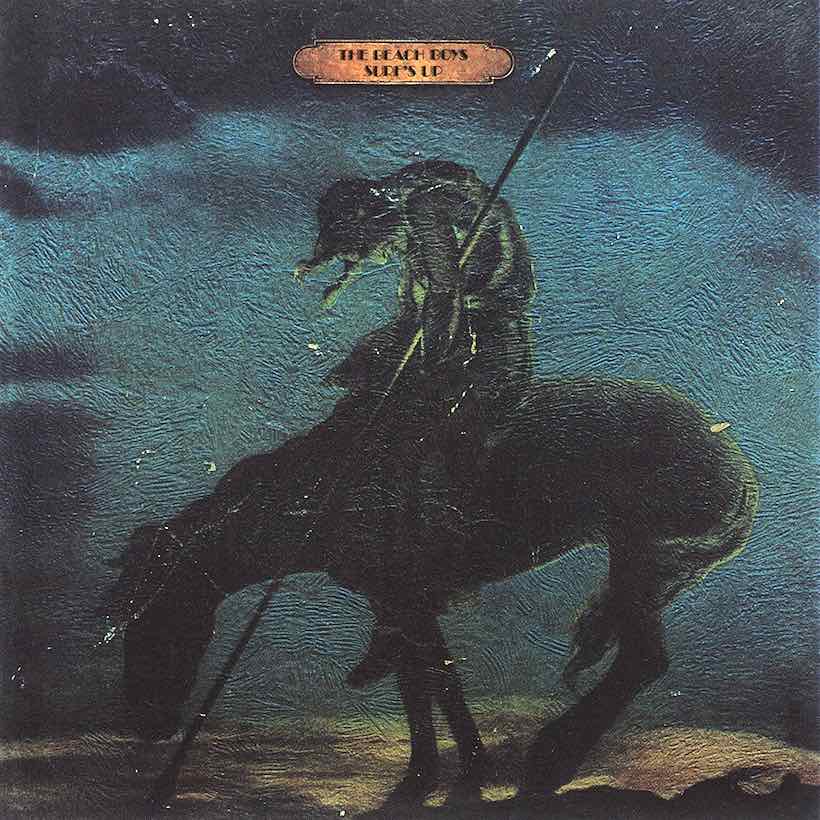

The Beach Boys advertised the release of 1971’s Surf’s Up with the slogan ‘It’s now safe to listen to the Beach Boys’. Following a period of commercial failure in the late 60s, Brian and the boys brought on Jack Rieley as their new manager, who formulated a plan to rebrand the group as an ‘ecological’ band who were in touch with the hippie counterculture. The ‘ecological’ album which came out of these efforts is an awkward masterpiece, one of their best albums almost in spite of itself. Some of its best songs (‘Disney Girls’, ‘Long Promised Road’ and ‘Surf’s Up’, the title track) bear little relation to Rieley’s vision for a politically urgent Beach Boys record. Whereas the album’s most straightforwardly political song, ‘Student Demonstration Time’, is a disaster – a smug and shallow blues tune about the state murder of student protesters.

Other songs which engage with politics and ecology are more successful, ‘Don’t go near the water’ is kind of goofy, but I’ve always loved its groove and Mike and Al’s vocals. ‘Till I Die’ is a beautiful Brian Wilson song which resolves thoughts of loneliness and insignificance into an ecological vision of oneness with nature.

I think ‘A Day in the Life of a Tree’ is the real standout song. Partly because of the decision to have new manager Jack Rieley take lead vocals: his croaky, fragile delivery stands out against the still angelic tones of the boys elsewhere on the album, and gives the song much of its haunting beauty. ‘Day in the Life of a Tree’ is an ecological song in a different way to ‘Don’t Go Near the Water’, although both songs deal with the effects of human pollution on nature. ‘Don’t Go Near the Water’ spells its message out in slogans:

‘Toothpaste and soap will make our oceans a bubble bath

So let’s avoid an ecological aftermath’

Whereas ‘A Day in the Life of a Tree’, like ‘Till I Die’, works towards its message by merging ecological pains with human ones. The narrative of the song works as an anti pollution message and as a portrait of human life - telling the story of a strong and happy adolescence before a troubled adulthood, a story that the music of the Beach Boys tells over and over again. In this way, the song functions effectively as properly ‘ecological’ art: not art about environmentalism, but art which blurs the boundaries between human and nonhuman nature and encourages empathy across that boundary.

Nunhead Cemetery is my favourite natural place in London. I love how overgrown and wild it is, how the gravestones and ruins have been swallowed up by the plants. The cemetery was opened in 1840 and stayed in use uninterrupted until the late 20th century, when it succumbed to neglect and was abandoned by its private owners. It was closed to the public between 1970 and 2001, and during that time the site became a vibrant and wild natural habitat. The cemetery is full of ornate Gothic memorials which have been reabsorbed into the landscape - webs of moss spread across stone angels. It’s a peaceful place, in part because of Nunhead’s separation from central London, but also because the huge trees seem to protect the cemetery in a kind of bubble. It barely feels like London at all, until a distant St Paul’s Cathedral suddenly appears through a gap in the trees.

Nunhead cemetery has a spooky appeal, but I think it’s also a very happy place. When lack of care left the site in ruins it transformed itself into a nature reserve, a more peaceful and noble resting place than the stiff Victorian cemetery it was built as, or the neglected site it became. This transformation was supported by the local community; the Friends of Nunhead Cemetery group organise volunteer conservation days, and work to protect the site as ‘a place of remembrance, of historic importance and of natural beauty’.

It’s a place in which human and nonhuman nature are merged and in harmony.

BFI Southbank / Love and Mercy (Brian Wilson ‘88)

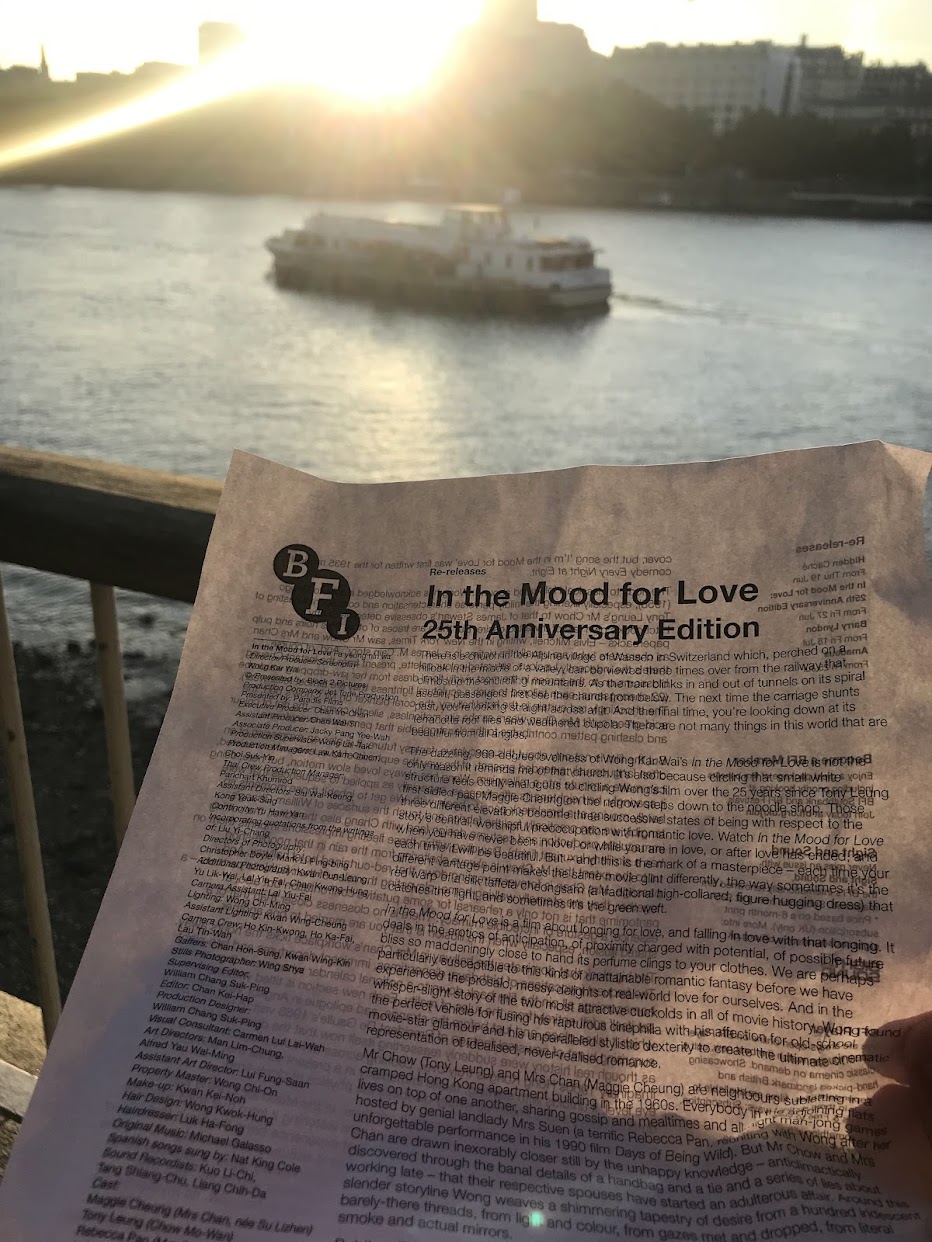

Before I moved to London, Southbank was probably the area I visited most often. When I was at school I went with friends to watch the skaters underneath the Southbank centre, and on school trips to the Globe and the Tate Modern. I can’t remember the first time I went to BFI Southbank, it might have been during the London Film Festival or maybe to see a restoration of The Outsiders, introduced via zoom by a grumpy Francis Ford Coppola. I’ve got happy memories of being there with friends but it’s most cherished to me as a place to come on my own; the tickets are cheap and the programming is reliably brilliant, so it’s one of my break in case of emergency happy places.

My favourite thing about watching films at the BFI is the sheet of paper you can pick up on your way into the theatre, with an essay on the film you’re about to watch. It’s nice to have the film framed in that way and I like that the experience is tied to something physical. My second favourite thing is that you emerge after a film directly onto the banks of the Thames, ideally just before sunset when the river and the buildings across the water are lit up orange. The initial connection I made to ‘Love and Mercy’ is a shallow one: in the first line of the song, Brian sings

‘I was sitting in a crummy movie with my hands on my chin’

I think there’s a deeper connection to be made though. ‘Love and Mercy’ became a signature song for Brian in the latter half of his life, its title became a personal mantra. It’s probably the best song he released under his own name, definitely the most popular and most enduring – but more than that, I think it reflects the way Brian saw the world more profoundly than anything else he wrote. The positive and compassionate message of the chorus is offset by its outsider perspective, love and mercy for the world from a position on its margins. In all three verses of the song, Brian sings about being an observer: watching a ‘crummy movie’, watching the news on TV, and watching people in a bar.

But it doesn’t feel like a song about loneliness or marginalisation, love and mercy wins out. I think you can hear this happening musically: the chorus, a perfect gem of Brian Wilson pop, refuses to go away, returning again and again in full earnestness. Even when the song dissolves into a bridge section of haunting chamber harmonies and minor chords, it only takes one shout of ‘HeyYy’ and we’re back. That second half of the song is perfect to me, it sums up everything I love about Brian and the Beach Boys - the ease with which their music crosses between two disparate emotional worlds, the ability and willingness to move from a tightly arranged passage of angelic wails directly into a catchy, twee pop chorus.

Going to the cinema on my own is often something I do when I feel lonely, maybe because the act of watching a film involves a room of people sitting in silence together, everyone having their own experience but hopefully sharing in one as well. Every time I leave the cinema I leave with a smile and a feeling of love and mercy.

Castle Leisure Centre / ‘Life is for the Living’ (Adult/Child)

‘Life is for the living’ would have been the first song on Adult/Child, an unreleased follow up to 1977’s Love You. It’s a very weird Beach Boys album (though in some ways they all are) in which Brian’s lyrics are backed up by a Sinatra style Big Band. ‘Life is for the living’ is an upbeat and optimistic song about working on yourself, which isn’t fully convincing: like ‘Love and Mercy’, the lyric ‘Life is for the living’ is a mantra which works to overcome dark forces at play elsewhere in the song, proclaiming the need to seize the day and appreciate life and not to ‘sit on your ass smoking grass’.

I tried to overcome some of my own sadness last year by getting up early and going swimming at the Castle leisure centre in Elephant and Castle. At the pool, you can book a 50 minute slot in the fast, medium or slow lane: I’d choose the medium lane because it felt like the safest bet, but found that it was a kind of pool purgatory, populated by the fastest slow swimmers and the slowest fast ones.

Life in the medium lane is a constant dance, you have to pick the right moment to join the rotation so that, ideally, you’re slower than the person in front and faster than the person behind. This equilibrium will hold for a bit, but it will inevitably collapse into chaos and you’ll have to overtake or allow yourself to be overtaken, or remove yourself completely from the cycle and re enter at a safe point. Such were my thoughts in the water, I managed to convert anxious energy into pool lengths and a theory of swimming.

As much as exercise does genuinely help me feel happier and less gloomy, it doesn’t work perfectly and old, less healthy patterns always re emerge. But it’s all about the effort, about trying to be better - which is what the song captures. Things get better, and then get worse, then get better again - and Brian’s ridiculous big band workout song brings me a lot of happiness, the huge belting cry of ‘LIFEEEEE’ at the end of the song in particular, which (in the Soundcloud bootleg of the album I listen to) leads straight into a song about baseball - that is the beauty of the Beach Boys.

Rotherhithe Beach / ‘River Song’ (Pacific Ocean Blue)

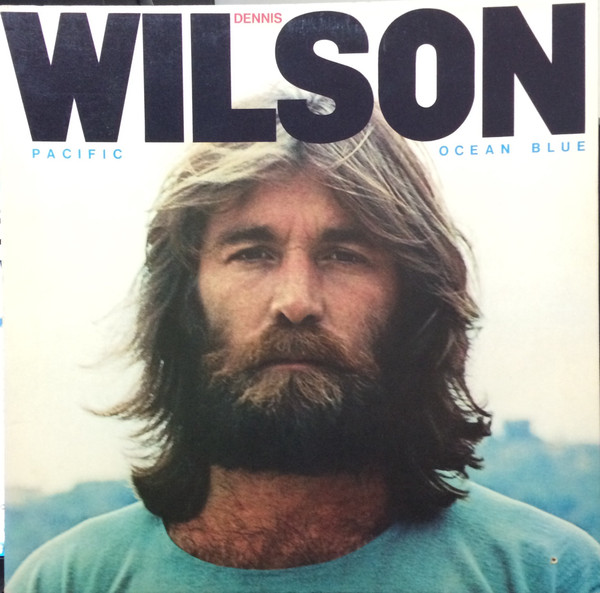

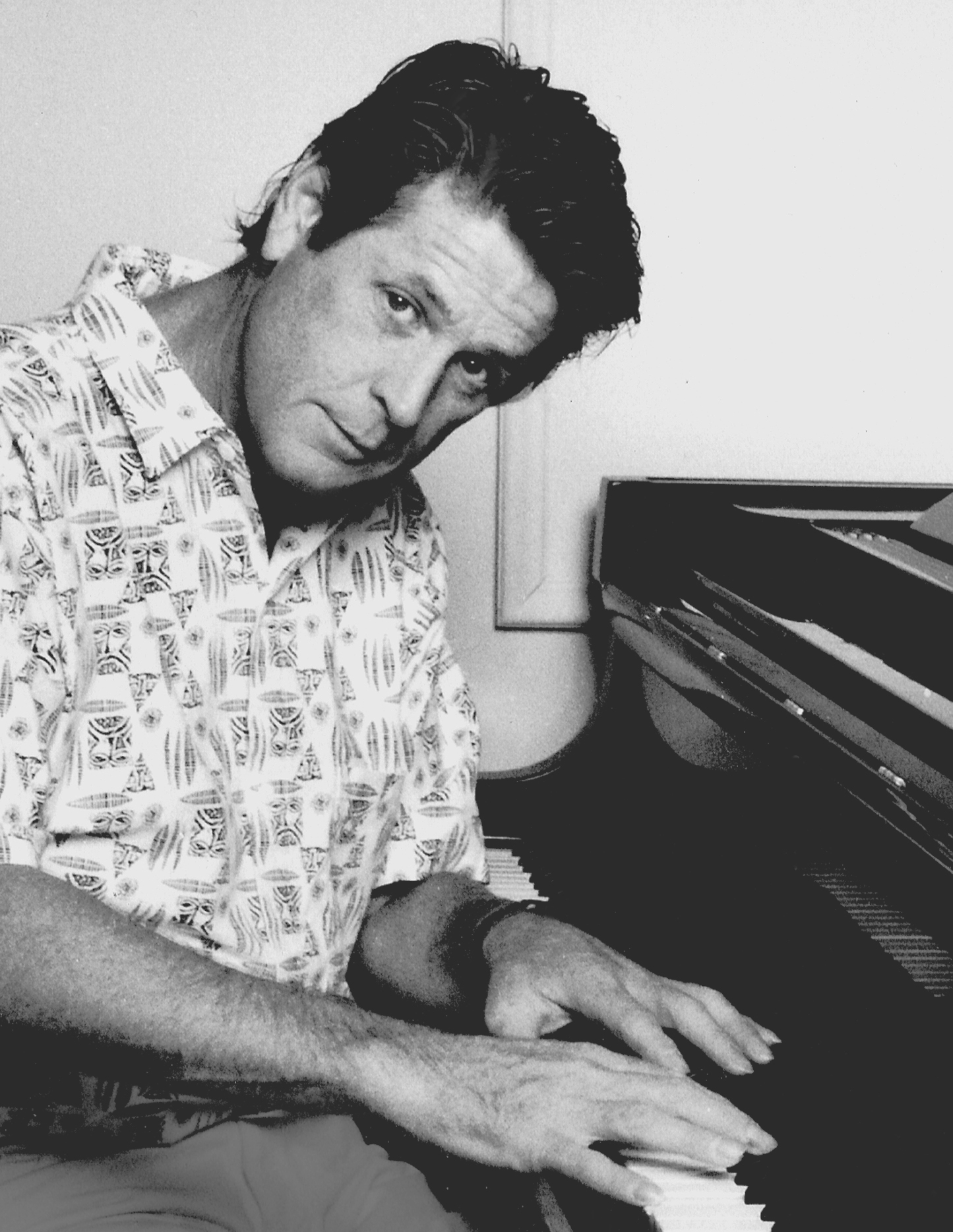

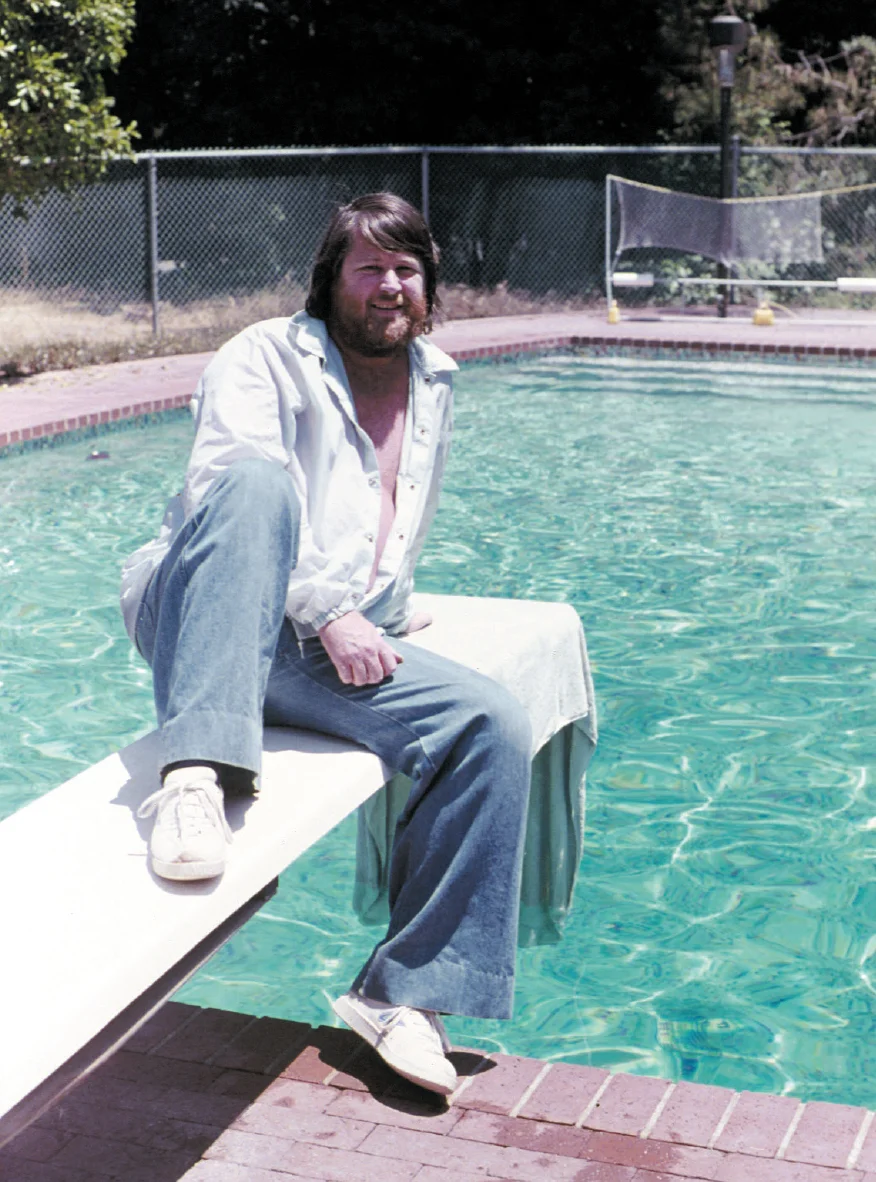

‘River Song’ was the first single that Dennis Wilson released as a solo artist, and the opening track on his debut solo album. Dennis’ life was tragically cut short at the age of 39, when he drowned while swimming in the harbour at Marina Del Rey. So ‘Pacific Ocean Blue’ remains the only Dennis Wilson album to be finished and released during his lifetime. The planned follow-up Bambu, was delayed and eventually shelved.

Bits and pieces were harvested for various Beach Boys albums, and the album was finally released in full, posthumously, in 2008. Bambu’s eventual release was tied to a reissue of Pacific Ocean Blue, which had steadily gained a cult following in the decades since its release, and is now regarded as one of the best albums of the combined Beach Boys discography, up there with the best Brian-led releases of the 60s and 70s.

Dennis’ life was hard, and full of troubles which were both unlucky and sometimes self inflicted. The fact that he was able to put together Pacific Ocean Blue, and ‘River Song’ in particular, from within this storm is testament to his talent and perhaps to the idea that there’s something uniquely special about the Wilson brothers. I love Pacific Ocean Blue because it’s great on its own terms: there are elements which nod towards to the signature Beach Boys sound, but for the most part it lives in its own unique world.

Many of Brian’s best songs involved scaling pop music to grand dimensions, on this album Dennis achieves a similar feat with funk music. It showcases the best of his drumming abilities, and makes great use of his damaged, gravelly voice - which is bolstered by some soaring background vocals. The arrangements on ‘River Song’ are dense and tall, proper wall of sound production, but at its heart the sound is founded upon a rolling, undulating groove. I genuinely don’t think it sounds like any other song, Beach Boys or otherwise, and it’s the stand out from Dennis’ brief solo career.

On the other hand, Rotherhithe Beach is one of many Thames beaches in London, but it was near to my first flat outside of uni halls and it’s my personal favourite. I love the ancient, cozy Mayflower pub around the corner, and the vibrant green algae on the flood walls lining the beach; I can always find washed-up ruined treasures among the stones, and the central London skyline is far enough away to look beautiful.

The docklands of South East London are long out of use, but I feel like the Thames still has a lingering impact over the area – everywhere feels tied to this great natural beast. The Thames beaches are all little outposts, pockets of wildness in the city. On ‘River Song’, Dennis sings about the alienation of living in a city separated from nature, and his desire for the freedom of a rolling river – I’m very thankful for the Thames and its beaches, it’s an endless source of motion and fortitude.